Sir John Soane House

ambiguity

Sir John Soane’s house is very close to the AA, in Lincoln’s Inn Fields; I used to visit as a student, when Sir John Summerson was still the curator, well before the 1988 restoration program returning it back to supposedly how it looked at the time of the 1833 Soane Museum Act which put the houses into a trusteeship, before Eva Jiřičná’s exhibition gallery, before the development of museum outreach as a concept for this site. It was dark, shadowed, empty, silent; often one would be the only visitor. It felt both infinite and intimate.

Nothing was labelled, nothing interpreted, you just wandered about looking at rooms and collections, probably missing important lessons but seeing things thought about ever after. Ian Nairn wrote in Nairn’s London of 1966, ‘After a visit here, four walls and a ceiling can never look quite the same’. Quite. Every surface was ambiguous: a wall panel would open out to reveal – a wall, doubling the surface; all the bits and fragments of classical sculpture caught the eye, the walls they were hung on receded. You found yourself looking not at the dining room but looking high up in the corners to the convex mirrors that reflected the dining room. No piece of wall was large enough to reveal its plane, so interrupted with events was it. Large spaces were made cramped with collections flung into them almost like detritus – interesting, possibly valuable; detritus nonetheless.

The Soane Medal is quite a recent thing; it started in 2017, six recipients so far, several of the whom have also received the Pritzker. David Chipperfield, a former Sir John Soane’s Museum trustee, leads the jury of architects, critics and curators, which perhaps gives a direction to the Soane Medal in that each recipient shares a focus on the local condition, social intervention and intense scrutiny of place and building. In order: Rafael Moneo, Kenneth Frampton, Denise Scott Brown, Marina Tabassum and Peter Barber, none of whose work has been declarative, but rather discursive, mutable, responsive.

Moneo came out of that flourishing of an elegant kind of architecture in the 1980s in counter-response to the previous four declarative and repressive decades of Franco’s Spain. Denise Scott Brown was the force behind Learning From Las Vegas, a stance so un-judgemental that she could find value in the most maligned environments and make of them lessons in intellectual humility. Kenneth Frampton charged several generations of architects and critics to think about place and weather, building traditions and land: critical regionalism. Marina Tabassum has spent her whole career in Bangladesh, bringing its building traditions and relationship to climate, geography, materials and deep sense of place to technology, large programs and modern urban life. Peter Barber’s practice has concentrated on social housing of great beauty in London. And Lacaton & Vassal’s work starts with close observation of lives lived within compressed and often benighted buildings.

These are emotional and passionate practitioners who bring these qualities to their architecture. Their medal lectures and brief encomiums, worth watching and reading to see each one’s reach, are on the Soane Medal webpage.

These qualities, emotion and passion, were anathema for the generations of architects trained in the 1960s to 1990s (probably earlier but I didn’t experience them), where clarity was all: the simple diagram that could be drawn on a paper napkin, a four-word description of the concept, the relentless application of the parti to all aspects of the project. Social concerns were considered naïve, ambiguity was a sign of weakness. A progressive erosion of such thinking started with Robert Venturi’s Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, published in 1961 not by an architectural press, but by the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It was followed by Venturi and Scott Brown’s Learning From Las Vegas in 1972, Collage City, 1978, by Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter that looked at the quality and use of interstices – the in-between, and Kenneth Frampton’s 1983 essay ‘Towards a critical regionalism: six points for an architecture of resistance’.

These are now old reference points; it is difficult to explain how revolutionary they were at the time when they confronted the near-monolith of the International Style of late capitalist modernism. Which we still have with us.

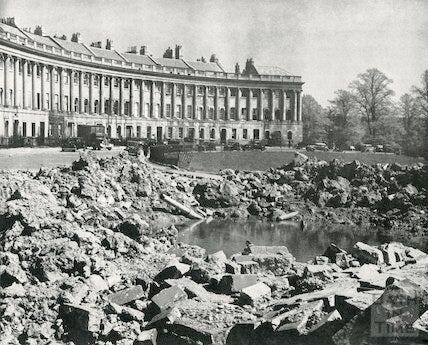

Soane’s house can be put into the context of other stellar examples of Georgian architecture. John Wood the Younger was the architect of the Royal Crescent in Bath, 1757-1774, finished just 18 years before Soane built his first house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Soane was the next generation, a slightly different sensibility.

In 1973 when I first saw the Royal Crescent, many of the houses had been divided into flats and cold water bedsits, several were hotels; some were squats, some remained as full houses. The crescent, the serene view, the processional fine grain of the fronts, its Jane Austen propriety, its Grade 1 listing (1950) were sort of waved away with a metaphorical hand and we were told to look at the backs instead. It was a lesson in distrust of the controlled image, a skepticism towards perfect beauty that is supported by something more real, less effortful.

Fifty years on this might seem a quaint lesson, one of many in contemporary architectural discourse, but also one that has a home in the awarding of the Soane Medal. Restless ambiguity isn’t in itself a goal; it is more an acknowledgement that both/and is more flexible than either/or, a coalition of parts and ideas is more responsive than a single position. Everyman has more ideas than the man.

I have to acknowledge Jack Long here, an activist architect and planner who I worked with in the late 1970s/early1980s. He studied at Penn after WWII, started his career in the 1950s with I M Pei, did a mid-career Masters in Planning degree at McGill with his 1973 thesis ‘Everyman the Planner’, and was a political force in Calgary.

Stephanie- Thanks for sharing this. I particularly appreciated this sentence: "Restless ambiguity isn’t in itself a goal; it is more an acknowledgement that both/and is more flexible than either/or, a coalition of parts and ideas is more responsive than a single position. Everyman has more ideas than the man." Very accurately put, especially when it comes to talking about architecture. Particularly with Royal Crescent. Your writing is a great reminder of this. :)