One of our readers, Anne O’Callagan, wrote to us about Chipperfield — ‘one of my favourite architects, I love Hepworth Wakefield gallery.’ Hepworth Wakefield, in Wakefield, West Yorkshire, 2003-11; busy ground floor, a floor of clear gallery spaces above – white, clean, minimal. Sloped ceilings/roofs with reflected clerestory light. Built to house its Barbara Hepworth sculpture collection, plus other curated exhibitions.

As white, clean gallery spaces go, not dissimilar to Chipperfield’s Turner Contemporary, although the sites are quite different, the complexity of the plan very different, but the relationship between art and the envelope in which it is seen is the same. There is an invisibility of building, almost nothing to distract from the work. Artists go to galleries to study the artwork within, architects go to study the architecture that supports, or doesn’t, the work within. We are architects, we tend to see buildings first if they are really good.

Turner Contemporary: earlier known as Tate Margate, a particularly unassuming art gallery, also in a smallish town with a reputation far beyond its immediate appearance. Turner painted in Margate and his early morning view, below, was described by John Landseer’s 1808 comment: ‘We had not imagined that any VIEW of MARGATE, under any circumstances, would have made a picture of so much importance as that which Mr. Turner has painted of this subject.’

Clearly Margate as a place (population 62,000) continues to surprise. It is the home base of Tracey Emin, her foundation and artist residency and exhibition space, TKE Studios.

Anyway, Chipperfield’s gallery is, again, almost invisible, both on the skyline and inside:

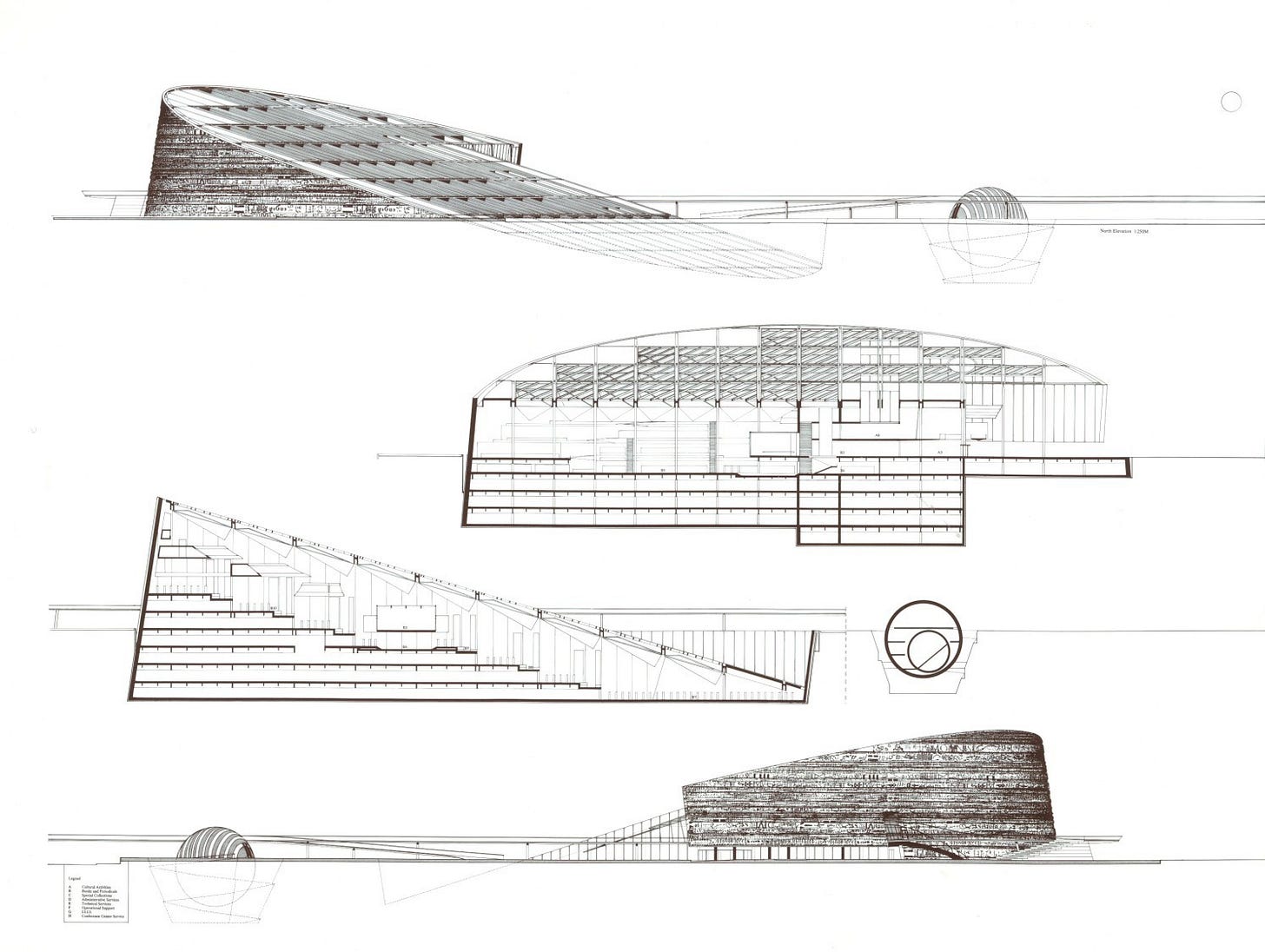

Turner Contemporary/Tate Margate started with an international competition in 2001, which was won by Snøhetta, the Norwegian architecture firm that first came to notice in 1989 when it won the competition for the Alexandria Library in Egypt with a dazzling half-submerged disc of a building.

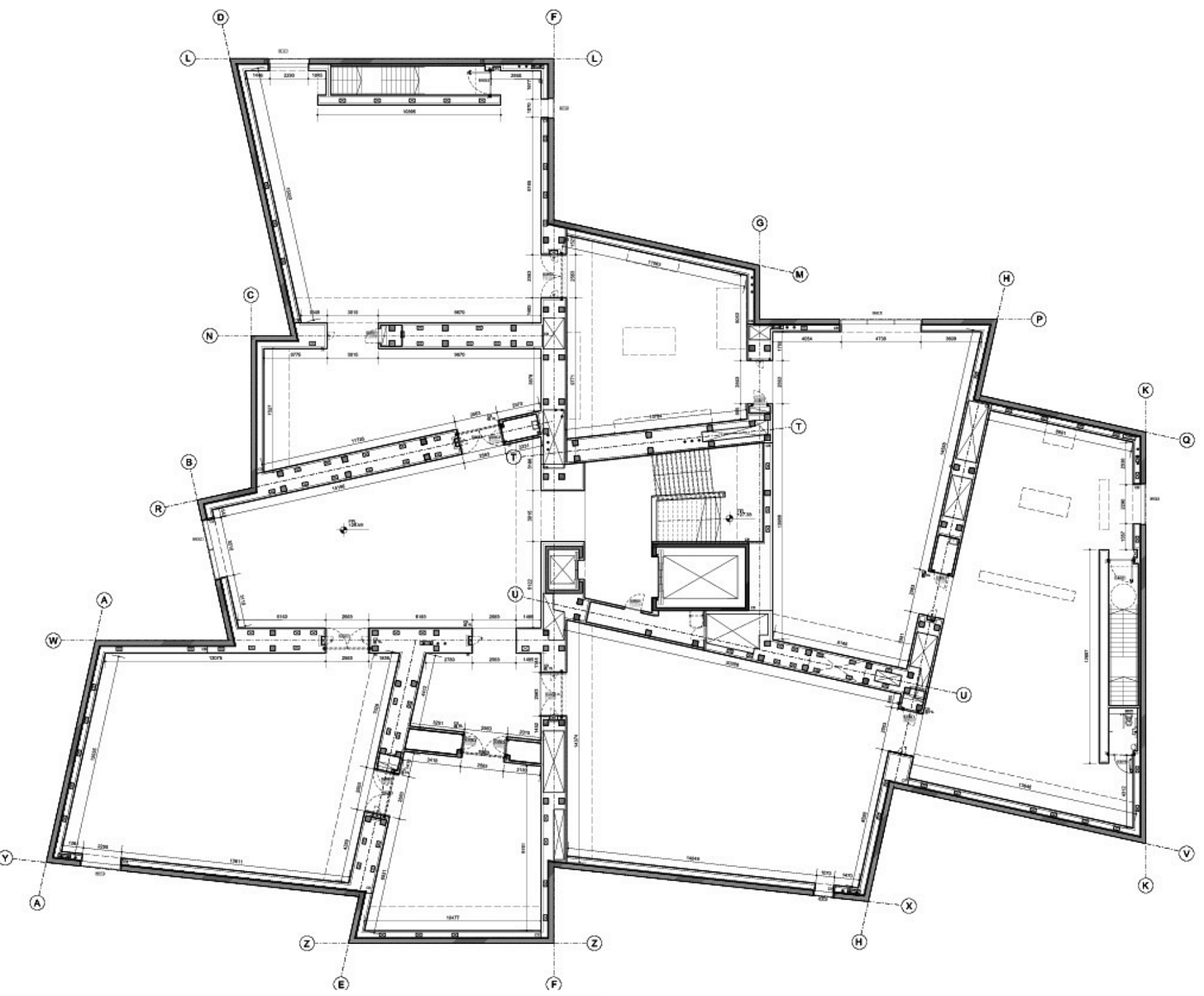

Snøhetta’s Tate Margate, of roughly the same time, looked like a giant wooden sail that billowed out over the sea in which it sat, pinned to a pier. On Site review 6: beauty published this project in 2001: the competition drawings, the layout board and text, sent from Jim Dodson, a student of mine in the early 1990s at the University of Texas at Austin, who had joined Snøhetta. There were links: Craig Dykers, who had also studied architecture at UTAustin, was a founding partner of Oslo-based Snøhetta along with Kjetil Thorsen. The project appeared beautiful, expressive of a wider landscape, and was, in the end, unbuildable.

A 2005 Guardian headline, after a test panel spiked into the seabed was blown apart in a storm, read ‘Gallery, 0; North Sea, 1’.

After several years of testing and redesigning, the project stopped, Kent County Council sued and Snøhetta eventually paid it £6 million compensation.

David Chipperfield was then given the project, which must have come as a great relief to all. No theatrics, no flooding hazard, safe in a storm.

Simple organisation: two large boxes, slightly offset from each other, and two smaller boxes at either end. North light comes in at the top; the building does its job in a most straightforward way. Little in the way of narrative, metaphor or other symbols. This, in itself, has a kind of elegance. It was also built on a parking lot supposedly lying over the place where a guesthouse Turner stayed in once stood. Mundane, but it was there, a flat site, not beautiful, ready to use.

Turner Contemporary doesn’t appear on Snøhetta’s website; it must have hurt to lose it. This project, Under, 2016-19, a building pinned to the seabed, half in/half out of the water, is a revisitation of the ambitions of the 2004-6 truncated Margate gallery. From Snøhetta’s website: In Norwegian, ‘under’ has the dual meaning of ‘below’ and ‘wonder.’ Half-sunken into the sea, the building’s 34m-long monolithic form breaks the surface of the water to rest directly on the seabed five metres below. The structure is designed to fully integrate into its marine environment over time, as the roughness of the concrete shell will function as an artificial reef, welcoming limpets and kelp to inhabit it. With the thick concrete walls lying against the craggy shoreline, the structure is built to withstand pressure and shock from the rugged sea conditions. Like a sunken periscope, the restaurant’s massive window offers a view of the seabed as it changes throughout the seasons and varying weather conditions.

Wonder versus utility. Complex ambition versus simplicity. The parameters of this particular and recurrent debate are problematic. Mending the relationship between an old part of town and the sea by removing an eyesore parking lot versus a heroic display of boundary-challenging construction. Keeping the architecture below the horizon versus it leaping up and hitting you in the eye. One sucks energy into intself, giving a building an overt dynamism – it demands attention from its environment. The other reflects energy back out from itself; it feeds its environment.

Is it possible that the 2023 Pritzker is an indication that we might like to shift away from an architecture of spectacle, shock, fragmentation, from buildings that look to be thrown off a cliff into the ocean? Everyday life is assailed by houses tumbling down newly eroded cliffs after new catastrophic storms, by the shock and spectacle of bombed-out cities, the fragmentation of our political systems and societies. We perhaps find replications of such excitements a bit wearying. After decades of challenging it, the centre is not holding.

The 2023 Pritzker has identified a calm, deliberate centre in a slow practice that seeks to mend and thread together difficult things. Chipperfield’s is not a new practice, but suddenly it seems a fit model for a reparative future.

Your analysis of human and cultural emotional movement, our reactions to architectures after political turbulence and climate disruption and the future needs we have from architecture, is comforting and sensible. You draw conclusions for this specific moment, and then surprise us with a turn from the submerged proposal for Margate dashed by storm and high tide, a center that does not hold, to reconstruction from old in Berlin. As much as we wish for the edgier solution, the building as curving sail, the result and its poetics can still surprise.