Paillote, Niamey, Niger. Straw matting hut, built in 1984. Lacaton & Vassal.

When students finish their architectural studies, the ones not deeply in hock to their student loans, often go travelling, or do a stint with an NGO in a distant, difficult country, paying back something for their privileged education, or following some idealistic model discovered during that education. After his studies at the AA in 1954, John F C Turner went to work in state housing in Peru, an experience primed by his student readings in Patrick Geddes, Lewis Mumford, and which, because of the lessons of squatter housing that he brought into housing policy, informed the rest of his life.

Jean-Phillipe Vassal, after graduating in 1980 from the École nationale supérieure d'architecture et de paysage de Bordeaux, spent five years in Niger as an architect and town planner. The Lacaton & Vassal website puts the Paillotte project, above, as their first project; it was also the first image in their 2023 Soane Medal lecture given at the end of November in the John Soane House library. As Vassal put it, the lesson was to build with the climate, not against it, and as one can see from all Lacaton & Vassal’s subsequent work, to build in a simple, unadorned, minimal way. For myself, I would put it as working with weak systems that combine to make mutable, flexible buildings: the willow that bends versus the oak that stands strong and is uprooted in the storm.

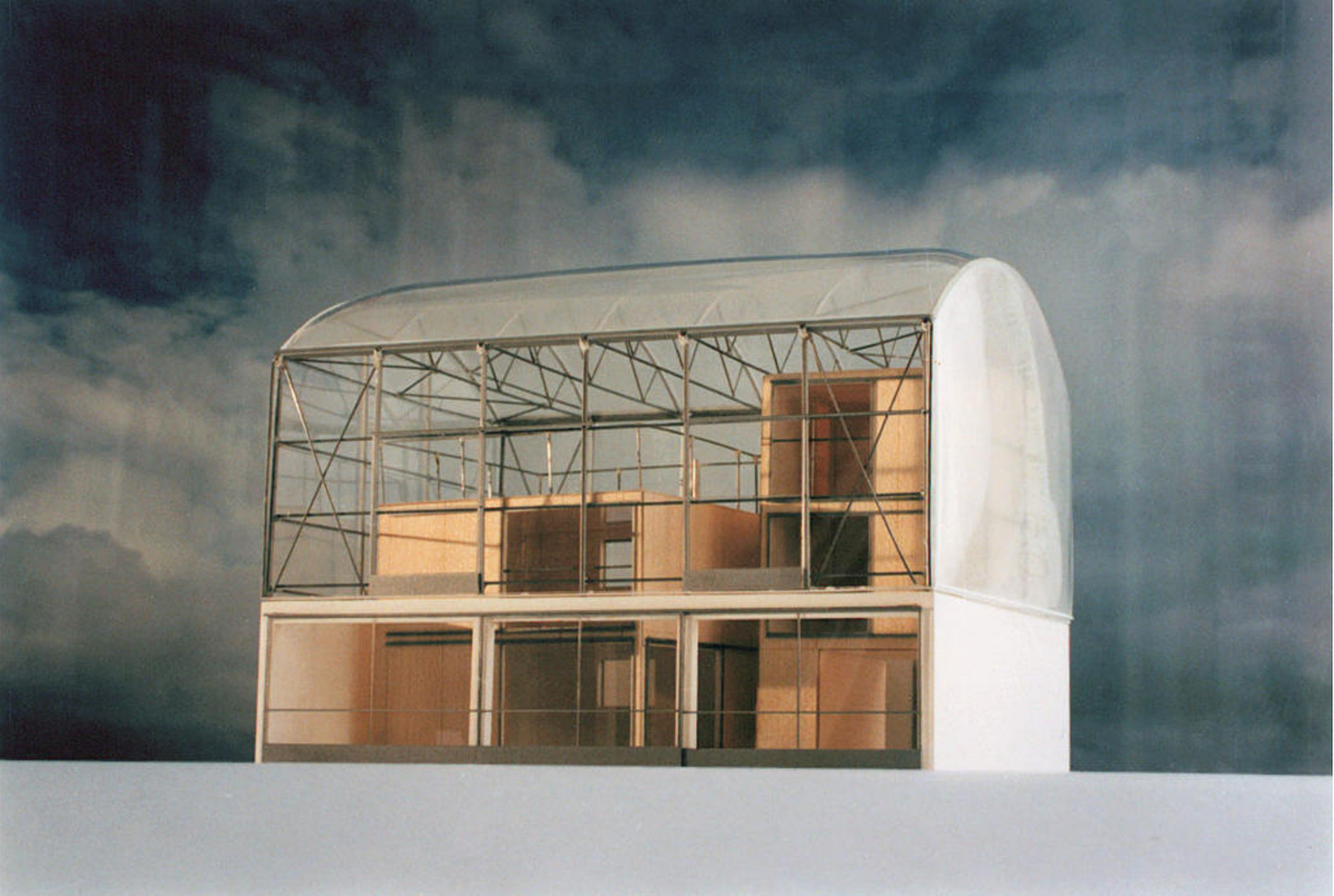

The second slide in the Sloane Medal lecture was of a large industrial greenhouse. Because these structures are designed for profitable agricultural use, they have highly developed material properties and climate control mechanisms. Built with stock material, simple in form, thy capitalise on climate and weather to provide an environment that hovers, mediates, occupies a liminal space, between inside and outside.

The second project on their website is a 1992 prototype dwelling: Maison d’habitation économique. Now clearly they were doing other kinds of work in the intervening eight years, but building a website for a practice is as much of a project as proposing a built structure. The narrative is designed, shaped, and in doing so, reveals the concepts at the very heart of Lacaton & Vassal’s much awarded and rewarded career.

Granted it was for the benign climate of the Balearics, and the cost estimate was more than planned, it still exhibits all the conditions and qualities found in Lacaton & Vassal’s work today.

This house on a small budget, gave Lacaton & Vassal their architectural modus operandi: build simply, build double, build with the existing, never demolish, always add.

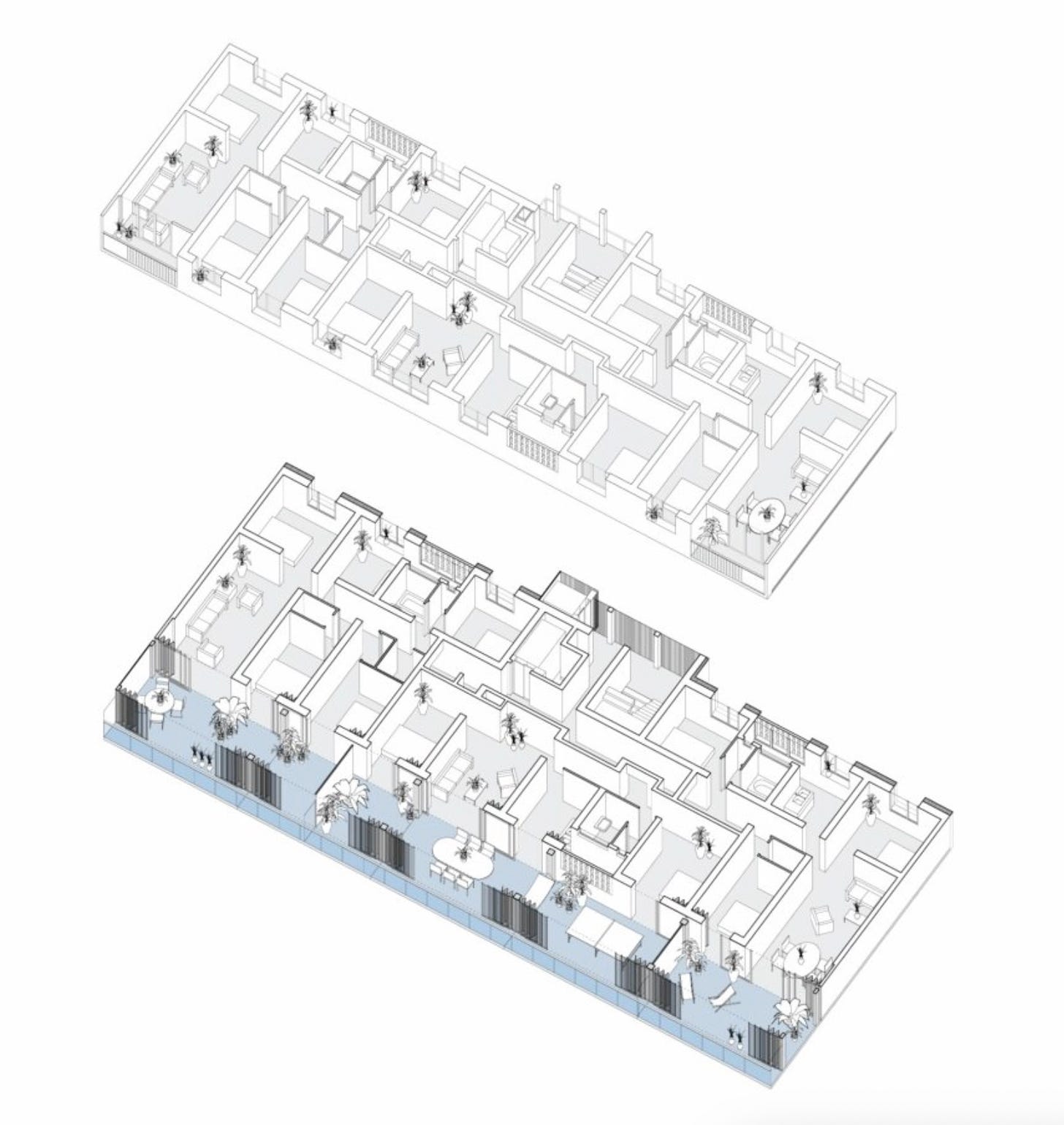

A large scale demonstration of building simply (read thinking clearly) was three 1960s social housing slabs in the Gran Parc estate in Bordeaux, slated for replacement in an ongoing rethink of social housing on city peripheries throughout France: partly a response to the social and ethnic problems particularly in the banlieus of Paris in the 1990s, and partly because their mid-modernist architecture was, and is still, much disparaged. Lacaton, Vassal and Pierre Druot challenged this initiative with their 2004 manifesto PLUS against wasteful demolition — it is unsustainable, a great loss of embedded energy and results in displacement and dispersal of inhabitants — and for the retention of the buildings, renewing mechanical systems, restoring structures if necessary, increasing the space of each unit and keeping the occupants of each block in place, in their units even through construction, next to their neighbours, in their neighbourhood of shops and transportation, near the schools their children attend.

Each of the 530 units had a full width 3.8m balcony added to its outside face: the old exterior wall was stripped off, the balconies glassed in with opening windows, sun-reflective curtains to be drawn or pulled back, a double-glazed interface at the unit itself. This, they call free space, unprogrammed, minimally conditioned, simply an enlargement of the existing flat, again a mediation between inside space and the outside environment.

There is a powerful economic reasoning underpinning this: for the Gran Parc 530 units, the cost of demolition and rebuilding new but smaller was €165,000/unit. Keeping and renovating each unit to be larger was €55,000/unit, a massive difference.

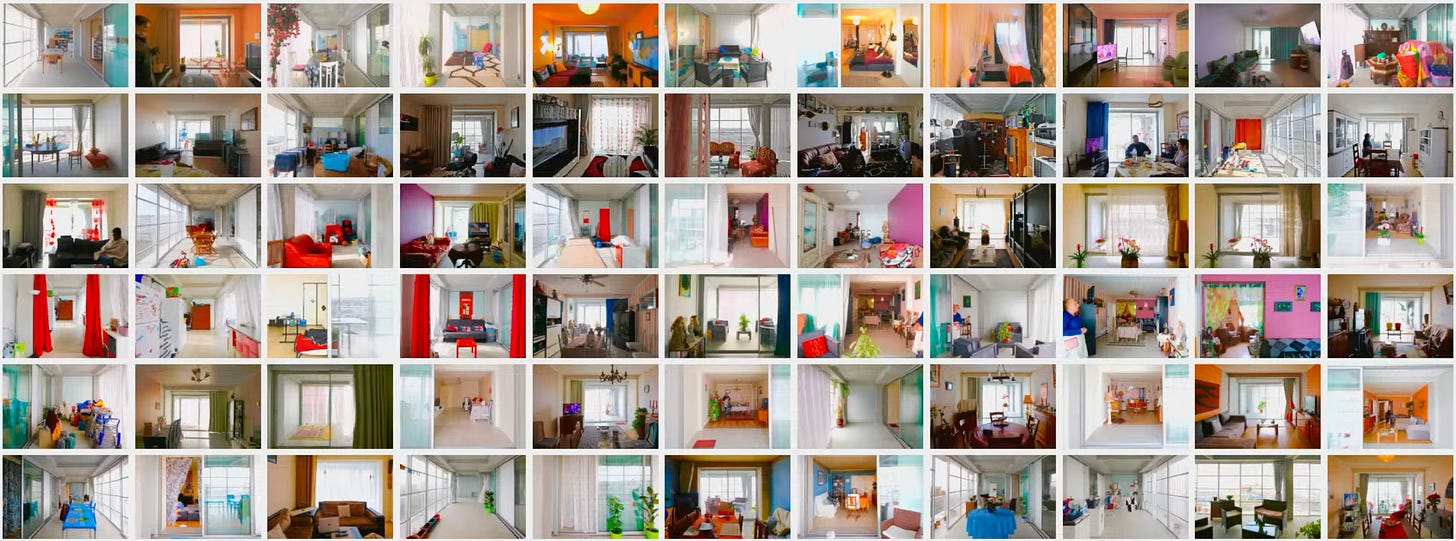

Anne Lacaton warns never to look from the outside and find a building ugly, look at people’s lives and collections inside, and start with that. Aesthetics and style are less important than the social intelligence that value comes from people and their lives, and that architecture’s task is to make those lives better.

free space

What Lacaton & Vassal call winter gardens occur in some form in all their projects from houses to housing, museums to universities, whether on roofs, or enormous terraces, or in doubled building volumes — unprogrammed space, willing to be appropriated for changing uses as needed or wanted. The advantage in not demolishing something, is that the structure already exists. It may be in rough shape, but that is remediable. It may not be perfect for whatever new functions are needed, but that pushes back on program, forcing it to interact with the past and the material present.

For new buildings and additions, Lacaton & Vassal build a basic concrete frame and platform structure, just as in their 1992 house prototype: the pre-condition for what they call loft space. On, in and around this structure is an environmental bubble, usually industrial greenhousing, mechanically vented, and within that is a basic building (for housing, inevitably following social housing standards) that sits like a piece of furniture in this enveloped loft space. Outside this programmed box is open space, nominally weather protected by the greenhouse system, but generally uninflected, unprogrammed.

These are free spaces, not technologically dependent, rather supplied with analogue opening windows, reflective curtains, shade arbours — things that require interaction to manage the space and its internal climate. Being unprogrammed releases users from conventional uses, from predictability and from the compression of tightly planned buildings. In the Soane lecture Jean-Pierre Vassal says ‘Open a window, draw a blind — don’t think of a building as a machine that does all of that for you. The building is like a body – change the coat according to the weather; change the functions with the seasons’.

It is these interactions that produce a deeply humanist architecture that builds less, observes more; is never cosmetic, nor does it make changes just for the sake of change.

Same as in Economics, win win.

I’m sure you’re aware of Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara’s concept of FREESPACE, which underpinned their curation of the 2018 Venice Biennale?